The souks of

Marrakesh sprawl immediately north of

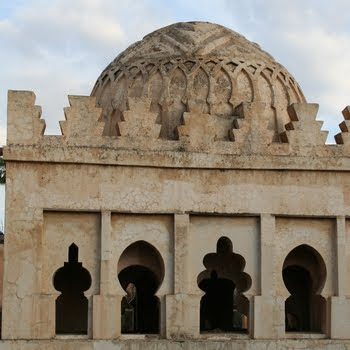

Dejmaa El Fna. They seem vast the first time you venture in, and almost impossible to navigate, though, in fact, the area that they cover is pretty compact. A long, covered street, Rue Souk Smarine, runs for half their length and then splits into two lanes - Souk El Attarin and souk El Kebir. Off these are virtually all the individual souks: alleys and small squares devoted to specific crafts, where you can often watch part of the production process. At the top of the main area of souks, too, you can visit the saadian Ben Youssef Medersa -the most important monument in the northern half of the medina arguably the finest building in the city after

the Koutoubia Minaret.

If you are staying for some days, you'll probably return often to the souks - and this is a good way of taking them in, singling out a couple of specific crafts or products to see, rather than being swamped by the whole. To come to grip with the general layout, though, you might find it useful to walk round the whole area once with a guide (see below). Despite the pressure of offers on Dejmaa El Fna, don't feel that one is essential, but until the hustlers begin to recognize you (seeing that you're been in the souks before), they'll probably follow you in; if and when this happens, try to be easygoing, polite and confident-the qualities that force most hustlers to look elsewhere.

The most interesting times to visit are in early morning (between 6.30 and 8am if you can make it) and late afternoon, at around 4 to 5 mp, when some of the souks auction off goods to local traders, Later in the evening, most of the stalls are closed, but you can wander unharassed to take a look at the elaborate decoration of their doorways and arches; those stalls that stay open, until 7 or 8pm, are often more amenable to bargaining at the end of the day.

Towards Ben Youssef : the main souks

On the corner of Dejmaa El Fna itself there is a small potters' souk, but the main market area begins a littel furthen beyoun this. Its entrance is initially confusing. Standing at the Café de france (and facing the mosque opposite), look across the street and you'll see the café El Fath and, beside it, a building with the sign "Tailleur de la place" - the lane sandwiched in between them will bring you out at the beginning of Rue Souk Smarine.

Souk Smarine and the Rahba Kedima

Busy and crowded, Rue Souk Smarine is an important thoroughfare, traditionally dominated by the sale of textile and clothing. Today, classier tourist "bazaars" are moving in, with american express signs displayed in the windows, but there are still dozens of shops in the arcades selling and tailoring traditional shirt and caftans. Along its whole course, the street is covered by a broad, iron trellis that restricts the sun to shafts of light; it replaces the old rush (smar) roofing, which along with many of the souks'more beautiful features was destroyed by a fire in the 1960s.

Just before the fork at its end, Souk Smarine narrows and you can get a glimpse through the passageways to its right of the Rabha Kedima, a small ramshackle square with a few vegetable stalls set up in the middle of it. Immediately to the right, as you go in, is Souk Larzal, a wool market feverishly active in the dawn hours, but closed most of the rest of the day. Alongside it, easily distinguished by smell alone, is Souk Batana, which deals with whole sheepskins - the pelts laid out to dry and be displayed on the roof. You can walk up here and take a look at how the skins are treated.

The most interesting aspect of Rabha Kedima, however, are the apothecary stalls grouped round the near corner of the square. There sell all the standard traditional cosmetic - earthenware saucers of cochineal (kashiniah) for rouge, powdered kohl or antimony for darkening the edges of the eyes, henna (the only cosmetic unmarried women are supposed to use) and the sticks of suak(walnut root or bark) with which you see Moroccans cleaning their teeth.

In addition to such essentials, the stalls also sell the herbal and animal ingredients that are still in widespread use for manipulation, or spellbinding. There are roots and tablets used as aphrodisiacs, and there are stranger and more specialized good -dried pieces of lizard and stork, fragment of beaks, talons and gazelle horns. Magic, white and black, has always been very much a part of Moroccan life, and there are dozens of stories relating to its effects.

La Criée Berbére

At the end of Rabha Kedima, a passageway to the left gives access to another, smaller square - a bustling, carpet-draped area known as La Criée Berbére (the Berbere auction) aka Souk Zrabia.

It was here that the old slave auctions were held, just before sunset every Wednesday, Thursday and Friday, until the French occupied the city in 1912. They were conducted, according to budgett Meakin's account in 1900, "precisely as those of crows and mules, often on the same spot by the same men ... with the human chattels being personally examined in the most disgusting manner, and paraded in lots by the auctioneers, who shout their attractions and the bids". Most had been kidnapped and brought in by the caravans from Guinea and sudan; Meakin saw two small boys sold for £5 apiece, an eight-year-old girl for £3 and 10 shilling and a "stalwart negro" went for £14; a beauty, he was told, might exceptionally fetch £130 to £150.

these days, rugs and carpets are about the only things sold in the square, and if you have a good deal of time and willpower you could spend the best part of a day here while endless (and often identical) stacks are unfolded and displayed before you. Some of the most interesting are the Berber rugs from the High Atlas -bright, geometric designs that look very different after being laid out on the roof and bleached by the sun. The dark, often black, backgrounds usually signify rugs from the Glaoui country, up towards Telouet; the reddish-backed carpets are from Chichaoua, a small village nearly half way to Essaouira, and are also pretty common. There is usually a small auction in the criée at around 4pm - an interesting sight with the auctioneers wandering round the square shouting out the latest bids, but it's not the best place to buy a rug - it's devoted mainly to heavy, brown woollen djellabas.

Around The Kissarias

Cutting back to Souk El Kebir, which by now has taken over from the Smarine, you emerge at the Kissarias, the covered markets at the heart of the souks. The goods here, epart from the many and sometimes imaginative couvertures (blankets), aren't that interesting; the kissarias traditionally sell the more expensive products, which today means a sad predominance of Western designs and imports. off to their right, at the southern end of the kissarias, is Souk des Bijoutiers, a modest jewellers'lane, which is much less varies than the one established in the Mellah by Jewish craftsmen. At the northern end is a convoluted web of alleys that comprise the Souk Cherratin, essentially a leather workers' souk (with dozens of purse makers and sandal cobblers), though it's interspersed with smaller alleys and souks of carpenters, sieve makers and even a few tourist shops. if you bear left through this area and then turn right, you should arrive at the open space in front of the Ben Youssef Mosque; the medersa is off to its right.

The Dyers' Souk and a loop back to the Djemaa El Fna

Had you earlier taken the left fork along Souk El Attarin - the spice and perfume souk - you would have come out on the other side of the kissarias and the long lane of the Souk des Babouches (slipper makers) aka Souk Smata.

The main attraction in this area is the little Souk des Teinturiers - the dyers' souk. To reach it, turn left along the first alley you come to after the souk des Babouches. Working your way down this lane (which comes out in a square by the Mouassin Mosque), look to your right and you'll see the entrance to the souk about halfway down - its lanes rhythmically flash with bright skeins of wool, hung from above. If you have trouble finding it, just follow the first tour group you see.

There is a reasonably straightforward alternative route back to dejmaa El Fna from here, following the main street down to the Mouassin Mosque (which is almost entirely concealed from public view, built at an angle to the square beside it) and then turning left on to Rue Mouassin. As you approach the mosque, the street widens very slightly opposite an elaborate triple-bayed fountain. Built in the mid-sixteenth century by the prolific Saadian builder, Abdallah El-Ghalib, this is one of many such fountains in Marrakesh with a basin for humans set next to two larger troughs for animals; its installation was a pious act, directly sanctioned by the koran in its charitable provision of water for men and beasts.

Below the Mouassin Mosque is an area of coppersmiths, Souk des Chaudronniers. Above it sprawls the main section of carpenters' workshops, Souk Chouari - with their beautiful smell of cedar - and beyond them the Souk Haddadine of blacksmiths - whose sounds you'll hear long before arriving.